Abstracts:

“Ruskin’s Dead Birds, Slow Violence, and the Time Scales of Artistic Extinction,” Interdisciplinary Nineteenth-Century Studies Annual Convention, Genoa, Italy, June 2025

This paper examines John Ruskin’s paintings of dead birds as visual enactments of what Rob Nixon terms “slow violence”—a form of gradual, unspectacular harm that unfolds across time and resists conventional modes of representation. While Ruskin famously insisted that animals should never be viewed from “the Butcher’s view,” several of his still life paintings—Dead Dove, Dead Wild Duck, Dead Pheasant—present animal corpses rendered with formal beauty and compositional care. Rather than treat these as contradictions, I argue that Ruskin’s paintings preserve the aesthetic residue of relational collapse. Drawing on Ruskin’s concept of the “Law of Help” in Modern Painters V, I show how he understood death as the moment when parts cease to support one another—whether in plants, moral systems, or artistic form. His dead birds, then, become elegies for lost interdependence: forms in which “help” has ceased, but its shape remains.

My talk will also explore the gendered implications of Ruskin’s suspended aesthetics. Victorian culture frequently figured women as birds—ornamental, fragile, and caged—and Ruskin’s paintings, when read alongside his mythic representations of Athena and Proserpina, evoke the feminized body as something preserved, moralized, and immobilized. Drawing on Sharon Aronofsky Weltman’s analysis of Ruskin’s symbolic destabilization of gender in Ruskin’s Mythic Queen, I suggest that Ruskin’s aesthetics of post-relational beauty encode both reverence and refusal: his birds are most beautiful when they can no longer help—or hurt—anyone. In this way, Ruskin’s visual ethics of death become a means not of mourning life, but of fixing it—transforming vulnerability into suspended form.

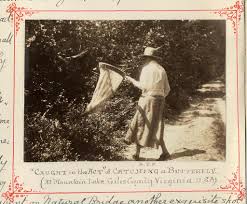

“Pursuits for Ladies”: Women Lepidopterists and the Genealogy of Collection,” Midwest Victorian Studies Association Annual Convention, Fort Wayne, April 2025

This paper examines how nineteenth-century women lepidopterists—particularly Margaret Fountaine and Eleanor Ormerod—challenge dominant genealogies of scientific knowledge. Scientific histories often center “founding fathers” and trace disciplinary lineage through masculine epistemologies: systematic publication, institutional affiliation, and objectivity. But what happens when the figure at the center is a woman? How does the work of science look different when it is tied not to conquest or capture, but to observation, curiosity, and care?

Using Margaret Fountaine’s twelve-volume diary, watercolor illustrations, and extensive butterfly collection as a point of entry, this paper explores how her scientific labor has been remembered, reframed, or erased. Despite collecting over 22,000 specimens across six continents, publishing in scientific journals, and being elected a fellow of the Royal Entomological Society in 1898, Fountaine was dismissed by contemporaries and later scholars as an eccentric amateur. By contrast, Eleanor Ormerod—who served in formal advisory roles and aligned her work with agricultural and institutional needs—was celebrated as an authority in economic entomology. Their juxtaposition reveals not a contrast in seriousness, but in visibility.

The paper draws on feminist historiography, including the work of Barbara Gates, Anne Shteir, Claire Jones, and Ornella Moscucci, as well as Michel Foucault’s theory of genealogical knowledge, to argue that scientific authority has always been structured by gendered expectations about who counts as a legitimate knower. Re-examining Fountaine on her own terms—through her diary, illustrations, and self-fashioned archive—allows us to question not only who does science, but who inherits it. Rather than adding women into an existing narrative, the talk proposes an alternative genealogy of collection—one that accounts for affective labor, amateur status, and the epistemologies embedded in overlooked forms of scientific documentation.